What We Do In Disasters

Grappling with what showing up looks like.

I spent about 10 days at the Eaton Fire in Southern California earlier this month, all 10 of which were spent in a climate-controlled trailer writing social media posts, media releases and website content about the fire for the regional office of the Forest Service. I basically spent 12 hours a day on my laptop, though I did drive into the fire area a few times—once to get my bearings and bear witness, and another to pass information along to the rifle-clad national guardsmen at the many blockades abutting the burn area.

I say this all to ensure that you don’t overestimate my role on this fire: I was a very VERY small piece of this puzzle, and while what I was doing was important in some abstract way that I can’t even clearly explain, I still felt all along like I wasn’t doing enough.

Maybe you’ve felt the same way recently.

I think a lot of us have felt this pent-up energy to do something and to be helpful over the last few weeks, and I’m guessing many of us came up short of what we think we should be able to contribute as the world burns. The problem is that with disasters like the Eaton Fire—which destroyed an unfathomable 9,400 homes and structures in the historically Black, working class community of Altadena—there is little you can do to truly help people in the ways they need to be helped. No matter what you do, there is still unimaginable suffering. No matter what you say, these folks are still on a journey few if any of us understand, and almost nothing can alleviate the many hurdles and outright injustices they will face on that journey.

Nevertheless, I watched my fellow PIOs (public information officers) do everything they could to reduce the suffering these folks were experiencing on a daily basis. Their main pathway to do that was to provide accurate, up-to-date information and then to simply listen. I watched as they came back from evac centers and disaster relief centers and hotels where evacuees are living, bearing the burdens of the people they spoke to throughout the day. I saw them going above and beyond their duties to sit with these folks, to truly listen to their concerns and experiences. I was moved, daily, by this team’s dedication to easing the losses being felt by an entire community turned to ash.

I was not interfacing with the community as much, but a day after I first drove through the devastation in Altadena, a fire friend of mine checked in to see how I was doing. He’d witnessed the Marshall Fire, and like everyone else who has witnessed the untold destruction of an urban conflagration, he knew the mental toll this stuff takes.

He started the conversation simply enough, asking how the fire was. I’d just gotten out of a peer support meeting, where we’d talked through some of the things we were experiencing, some of the heavy interactions we’d had, while the peer support folks gave us some mechanisms for handling the complex emotions that come up in these situations. With this as the backdrop, I kinda laid it on him—

“Good, weird, horrific, all at once,” I responded. “I like my assignment, but I wish I could do more. I feel guilty because everyone else is handling other people’s trauma all day, and I’m just in here writing my little stories.”

It was a pity party, to be sure, but he responded thoughtfully:

“I mean, all we can really do is tell our little stories because that’s the only thing we have control over.”

Stories do matter, even if they don’t always feel like it. Maybe my story on this fire was witnessing the selflessness of the people on the PIO team who at times seemed to be bearing the weight of an entire community’s grief. Maybe it was just witnessing—the devastation, the subsequent community care and staggering mutual aid response, the people living through more loss than most of us can imagine.

And yet I couldn’t kick the feeling that, surely, there was something more helpful I could be doing. And I think this feeling is worth exploring, because I don’t think many of us understand how we will need to show up in disasters or moments of massive community need or political turmoil, and I think even fewer of us will understand that sometimes the ways we’re needed will not feel especially fulfilling, in the ways that we expect helping to feel.

Not all of us can chase the glint and glory of boots-on-the-ground work like fire/ems or search and rescue, nor should we go rogue to chase the types of romanticized, heroic action that we’re often shown in disaster movies. The roles that actually, quantifiably make a difference in disasters don’t require muscles or brawn or god forbid guns; rather, they require an unwavering, daily commitment to community and collaboration, a willingness to take direction and do what is needed regardless of what that is, and pursuing specialized training that can help support specific post-disaster processes (think paperwork, case work, relationship building, and managing donations and volunteers).

My point is that these disasters are going to require something different from all of us, and some of those things may feel trivial based on our preconceived notions of what is “helpful” in these scenarios. We may need to reframe how we intend to show up when shit hits the fan. Some of us will almost certainly need to consider how a disaster will look in our own community, and begin preparing a seemingly boring skill set to prepare for it—think grant writing, technical assistance and disaster case management.

But help isn’t always synonymous with technical skills. Communities and survivors in the recovery phase will need basic support too—things like someone to drive them to appointments, someone to shop for them, someone to watch the kids while they deal with the many small crises that come up during big crises. Maybe it’s helping older folks fill out online forms. Maybe it’s delivering food to evac centers. Maybe it’s even more simple than that.

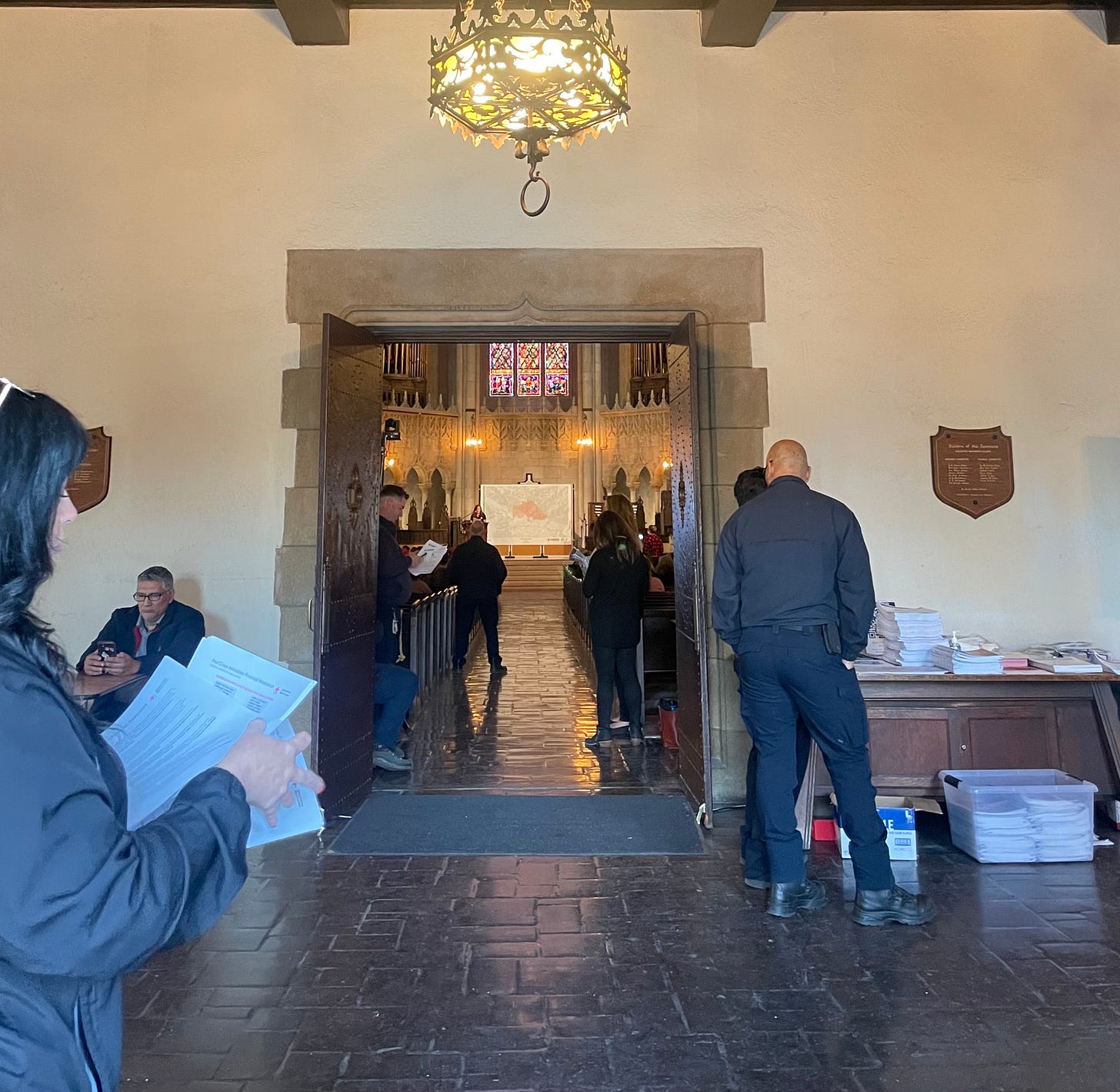

When I think of my own time on the Eaton, I can recall a few moments where I did feel genuinely helpful, and yet most of these moments were fleeting and relatively trivial—greeting and handing waters out to evacuees at a community meeting, making a tea for a fellow PIO who’d been in the field hearing first-hand accounts of a community torn apart, and clearly feeling it. And then I recall moments where others helped me with similarly minor actions: my friend who sent a simple text and allowed the conversation to go where it needed to go; the barista manning a coffee table at fire camp, who helped me fill my coffee mug when my hands were full, who asked me how I was and actually listened, who smiled so genuinely as I answered. All of these tiny interactions were laced with an understanding that everyone here was going through it in some way, big or small, and that the least we could do was be kind to each other in the process.

What I’ve realized is that a major part of preparing for and living through seemingly relentless disasters—whether you are impacted by, responding to or simply witnessing them—is accepting all that you can’t do, and then doing whatever little bit you can anyways. We will not all have big, glorious roles when disaster comes for us. Sure, some will need to be on the front lines doing the tangible, in-your-face work—fighting fires, giving medical aid, cleaning up debris, rebuilding. But the vast majority of us will be called to do the behind-the-scenes stuff: donating what we can, checking in on our friends experiencing it first hand, fulfilling critical but often unseen administrative roles, providing basic support to our community members. And yes, some of us will need to tell our little stories. And some of us will just need to listen.

Thanks to Dr. Crystal Kolden and Riley Yuan for their help with this.

Amanda well spoken, as someone who does international response, we are often in and out in 2-3 weeks and often carry around the thought of how family X is doing, did the team behind me follow through. Thanks for putting it into words

Writing little stories can feel like shouting into the void (hi, I hear you!!), but this post feels like balm on my lil' chapped heart today. Thank you for your words and your work; it's important and needed today and every day ahead of us.

“The roles that actually, quantifiably make a difference in disasters don’t require muscles or brawn or god forbid guns; rather, they require an unwavering, daily commitment to community and collaboration, a willingness to take direction and do what is needed regardless of what that is, and pursuing specialized training that can help support specific post-disaster processes (think paperwork, case work, relationship building, and managing donations and volunteers).”

^^ that hits especially hard.